Concubines

Selecting partners

Women were selected as xiunu (elegant females) for the court as early as the Jin Dynasty (265-420 AD) and the selection criteria ranged from emperor to emperor. In the Ming dynasty, for example, no household was exempt from the selection. According to statutes, all young unmarried women went through xiunu selection process. Only girls who where married or with certified physical disabilities or deformities were exempt.

But the Qing Emperor Shunzhi (1638-61) began to exclude most of the Han population by limiting selection to "Eight Banners" families, who were mainly Manchurian and Mongolian. (Eight Banners was a Manchurian administrative and military framework.)

The Board of Revenue sent notices to officials in the capital and provincial garrisons to enlist the help of clan heads. The banner officials then submitted a list of all available females to the commanders’ headquarters in Beijing and to the Board of Revenue. The Board of Revenue then set the date for selection.

REQUIREMENTS FOR SELECTION

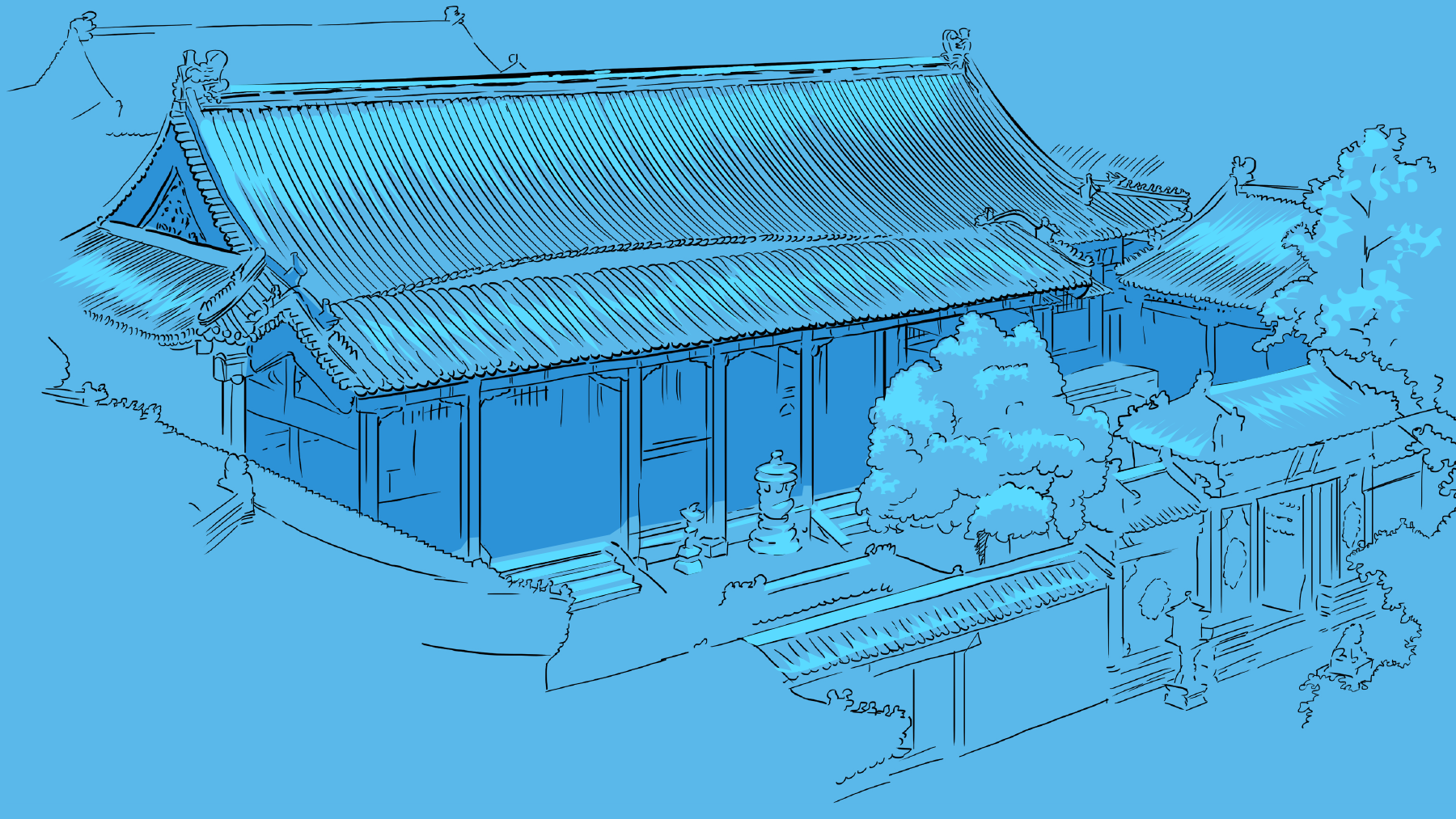

During the Qing dynasty, girls were brought on the appointed day to the Shenwu (Martial Spirit) Gate of the Forbidden City for inspection. They would be accompanied by their parents, or nearest relatives, together with their clan heads and local officials.

During the first round of the competition, the women stood in lines of 100 according to age

One thousand were eliminated for being too tall, short, fat or thin

On the second day, the eunuchs intensively examined the women's bodies, and evaluated their voices and general manner. This slimmed down the field by another 2,000

The third day was spent observing their feet and hands, and grace of movement. Another 1,000 were eliminated

The remaining 1,000 underwent gynaecological examinations, dismissing another 700 from the process

The remaining 300 were then housed in the palace where they underwent a month-long series of tests for intelligence, merit, temperament and moral character

The top 50 candidates were subject to further examinations and interviews about maths, literature and art, and ranked accordingly

The three favourites would receive the highest ranking for imperial concubines

Only a few of those who made it through this rigorous process would be noticed by the emperor and win his favour. Most would spend their lives in bitter loneliness, and unsurprisingly, politics and jealousy was rife among concubines. Beauty was more of a curse than a blessing in China during this period of history.

ACTIVITIES

Naturally, concubines were strictly forbidden from having sex with anyone other than the emperor.

Most of their activities were overseen and monitored by the eunuchs, who wielded great power in the palace. Concubines were required to bathe and be examined by a court doctor before the emperor visited their bed chamber.

With hundreds, and sometimes thousands, of concubines at the emperor’s disposal, any lady the emperor graced with a visit would be subject to jealous rivalries. Concubines had their own rooms and would fill their days applying make-up, sewing, practising various arts and socialising with other concubines. Many of them spent their entire lives in the palace without any contact with the emperor.

HIERARCHY

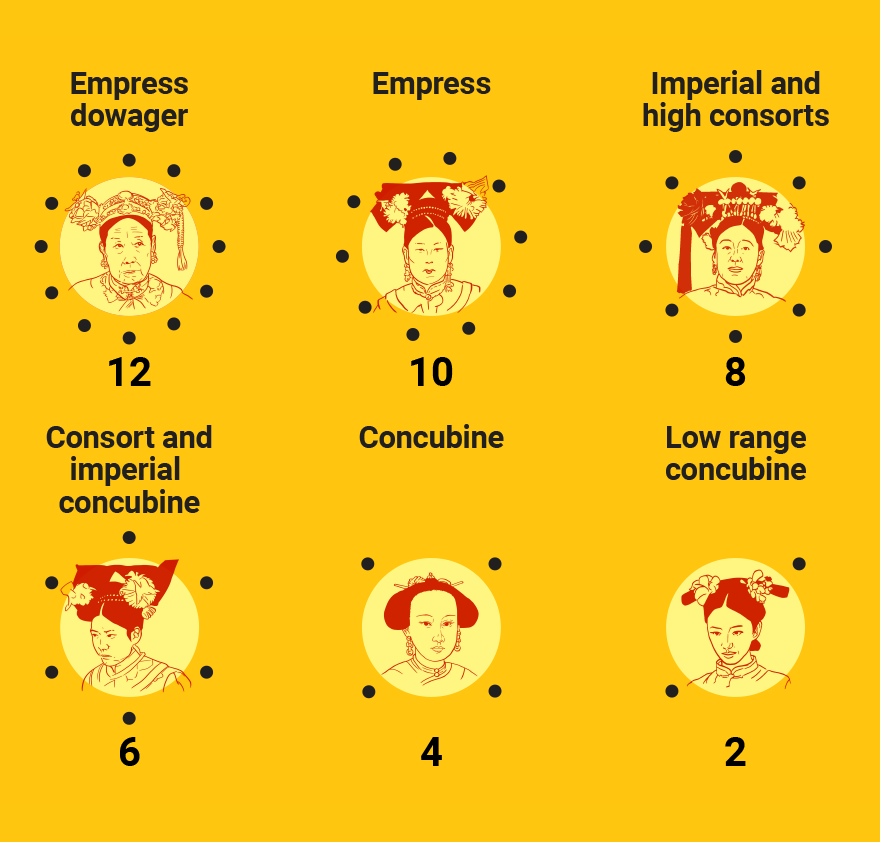

Qing Dynasty harem system

The ranking remained consistent but the number of consorts and concubines varied under different emperors

POLYGAMY

Polygamy was common practice in feudal China, although only upper- and wealthy middle-class men could afford to take several wives. It was seen as an affirmation of male potency, and the presence of many women was taken to indicate a man’s virility.

The emphasis was on procreation and the continuity of the father’s family name. Confucianism emphasised the ability of a man to manage a family as part of his personal growth in daxue (great learning). In the case of the emperor, guaranteeing a successor to the throne was of paramount importance.

1. The strict distinction between main wife and concubines

The main wife was superior to all other wives. She was responsible for submitting to the higher principles of polygamy and to mentor the other wives in harmonious behaviour for the greater good.

2. Women must not be jealous

Women, especially the main wife, had to rise above their earthly emotions. The belief that they were living for a higher purpose presumably helped displace feelings of bitterness, jealousy and rivalry.

3. Attachment could radically destabilise polygamy

The husband should not have a favourite, nor should any of the wives monopolise the man. Love had to be distributed evenly among the wives, which effectively meant that passionate attachment was not acceptable.

4. Polygamy could only survive by observing a strict hierarchy

Each dynasty had its own set of titles and ranks for the imperial wives. The empress ranked at the top, with more wives filling successive echelons below her. Most wives occupied the lower echelons. Hierarchy was determined at specific times, such as when a new wife joined the imperial family and was assigned a rank.

EMPEROR’S SEXUAL ROTATION

It was believed that organising the emperor’s sex life was essential to maintaining the well-being of the entire Chinese empire. The Chinese calendars of the 10th century were not used to keep track of time but rather to keep the emperor’s sex schedule in check. The rotation of concubines sleeping with the emperor was kept to a regimented order. Secretaries were employed to record the emperor’s sex life with brushes dipped in imperial vermilion.

MOON CYCLE

In China, and some other Asian countries, age is determined from the moment of conception, not the moment of birth. The Imperial Chinese believed that women were most likely to conceive during the full moon, when the Yin, or female influence, was strong enough to match the Yang, or male force, of the emperor. The empress and other wives slept with the emperor around the time of the full moon because it was believed children of strong virtue would be conceived on those nights. The lower-ranking concubines were tasked with nourishing the emperor’s Yang with their Yin, sleeping with him around the time of the new moon.

THE FATE OF A FAVOURITE

Zhenfei entered the palace in 1899 during the Guangxu reign at the age of 13. She was later promoted to the title of imperial concubine, second to Empress Longyu, who was the niece of Empress Dowager Cixi. Zhenfei was a beautiful and intelligent woman. As the Guangxu emperor’s favourite consort, she gained much influence in the imperial court. Popularly known as the “Pearl Consort”, she hated rules and regulations. She was prone to acts of rebellion which infuriated Cixi, who began to look for an excuse to punish her.

On June 20, 1900, the Eight-Nation Alliance laid siege to Beijing and Cixi forced the emperor to flee with her to Xian. Before they left, Cixi ordered Zhenfei to commit suicide on the pretext that her youth and beauty would endanger the royal party as well as bring shame if she were raped by foreign soldiers. Zhenfei refused, asking instead for an audience with the emperor. It is believed Dowager Cixi responded by ordering eunuchs to throw Zhenfei to her death down a well behind the Ningxia Palace.

Palace servants

The Qing Palace Maids

Maids were female servants in the palace. They were ranked according to their families’ social position and they would only be recruited from the Eight Banners families that were mainly Manchurians and Mongolians. They were selected when they reached the age of 13. Their role was to attend to the daily needs of the empress, imperial consorts and concubines. They could not leave their ladies’ sides, day or night, seven days a week. The maid-in-waiting held the highest rank.

MAIDS ASSIGNATION

The number of maids assigned to high-ranking women varied

WET NURSES

Imperial consorts and concubines wanted to mark their high status and spare themselves the physical challenges of breastfeeding. This resulted in wet nurses coming to high prominence during the Ming dynasty.

THE SELECTION

One of the more unusual responsibilities that the Rites and Proprietary office bestowed upon eunuchs was to recruit between 20 and 40 lactating women every three months.

Whenever a baby was due in the palace, 40 wet nurses and 80 substitutes were employed. Imperial sons were breastfed by a wet nurse whose own child was a girl, and vice versa in the cases of imperial daughters. This way the yin and yang could be matched and the substitution of babies, accidental or otherwise, could be averted.

REQUIREMENTS

When working, wet nurses received a clothing allowance, rice with about five ounces of meat a day, and coal in cold weather.

Royal princesess

Women in the imperial family

The emperor’s unmarried female relatives were not allowed to live outside the inner palace.

RANK METHODOLOGY

Imperial daughters were ranked according to their bloodline to the emperor and their mother’s title.

THE OTHER WAY TO BECOME A NOBLE

Other male members of the nobility looking for wives and concubines also had access to the xiunu (beauties) from the Eight Banners families. Lists of candidates were made and presented to the palace in groups of three or five. Those selected would either become palace concubines, be married to either the emperor’s sons or grandsons, or be married to princes and dukes and their sons and grandsons. Empresses came from this rank of “beauties”.

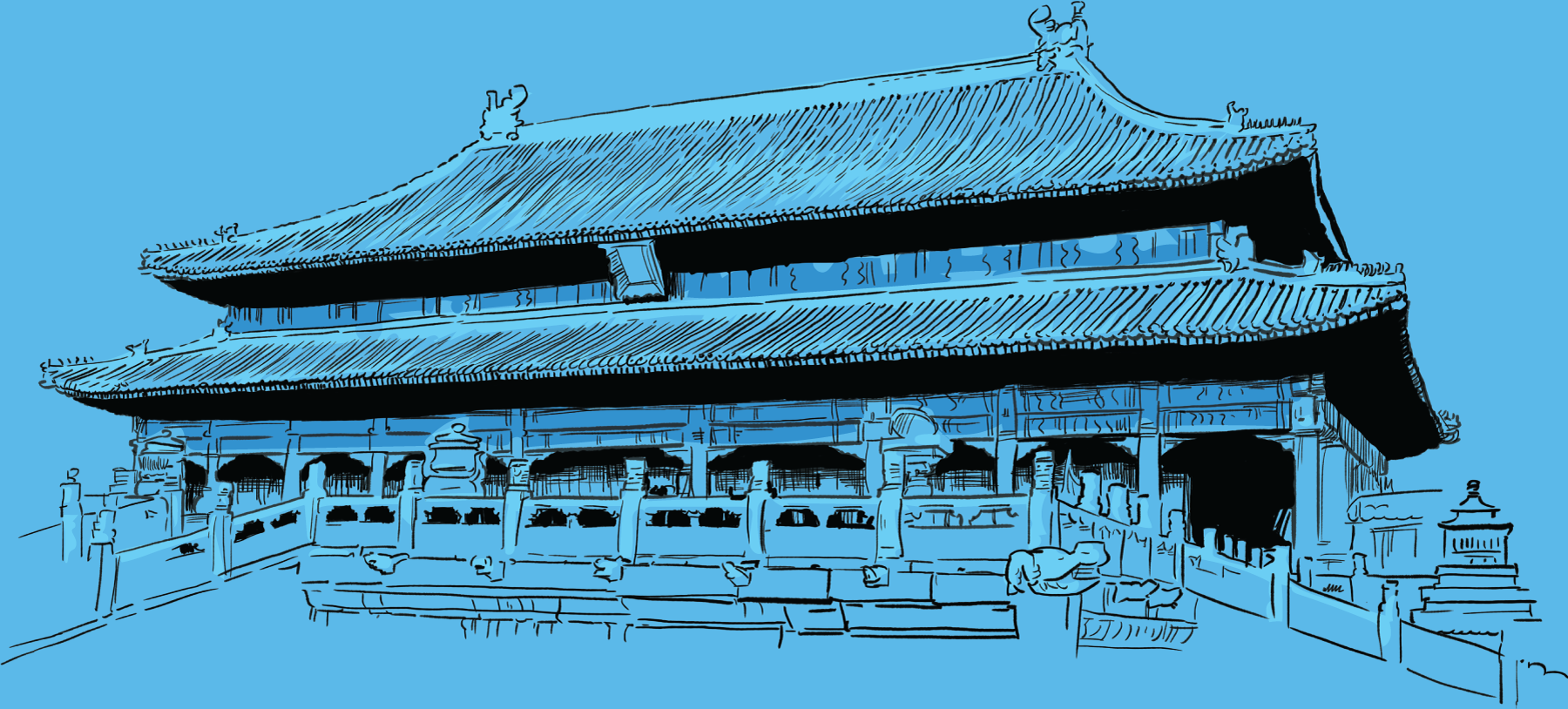

Life inside the Forbidden City

chapter 2

How an army of eunuchs ran the Forbidden City

JULY 23, 2018

Marcelo

Duhalde

The presence of eunuchs in the Chinese court was a long-standing tradition. These emasculated men served as palace menials, spies and harem watchdogs throughout the ancient world. An army of eunuchs was attached to the Forbidden City, primarily to safeguard the imperial ladies’ chastity.

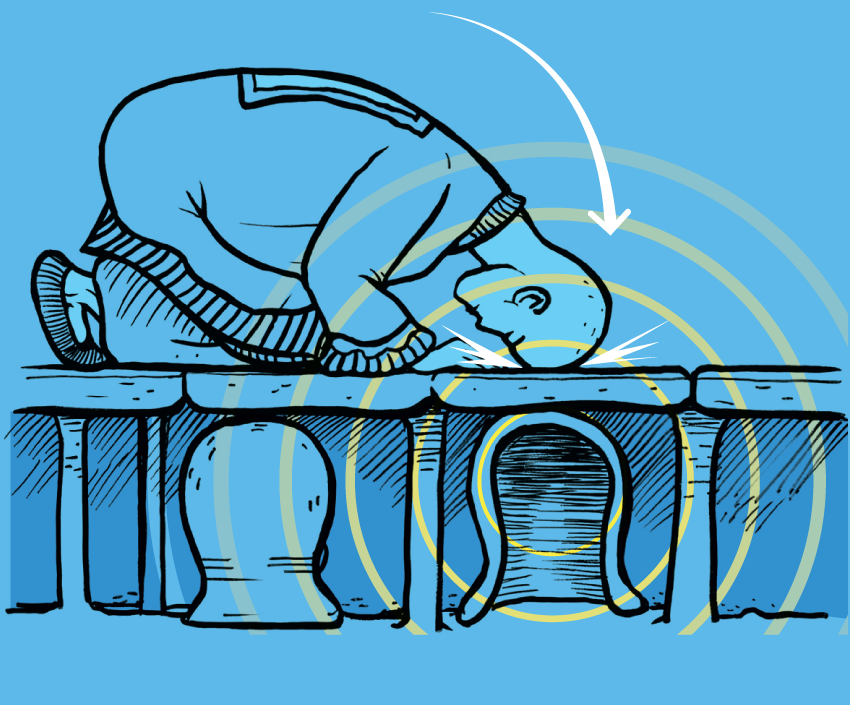

About an eighth of those who became eunuchs were young children bowing to parental pressure. Families would receive a cash reward for donating their sons, but they also hoped their children would have a more comfortable and prosperous life in the palace

About an eighth of those who became eunuchs were young children bowing to parental pressure. Families would receive a cash reward for donating their sons, but they also hoped their children would have a more comfortable and prosperous life in the palace Some adults, with no economic means to lead an honest and acceptable way of life, preferred emasculation to a life of begging and stealing

Some adults, with no economic means to lead an honest and acceptable way of life, preferred emasculation to a life of begging and stealing  Some men, who could only envision a life of futility and hardship, were envious of the seemingly easy lifestyle enjoyed by palace eunuchs

Some men, who could only envision a life of futility and hardship, were envious of the seemingly easy lifestyle enjoyed by palace eunuchs Emperor Guangwu of Han (reign between 25 and 57 BC) commuted all death sentences to emasculation and successive emperors followed this edict

Emperor Guangwu of Han (reign between 25 and 57 BC) commuted all death sentences to emasculation and successive emperors followed this edict